The chickens are fascinating for me to watch because of the way they move. Whereas mammals tend to move in a continuous flow, avians tend to move jerkily and seemingly instantly.

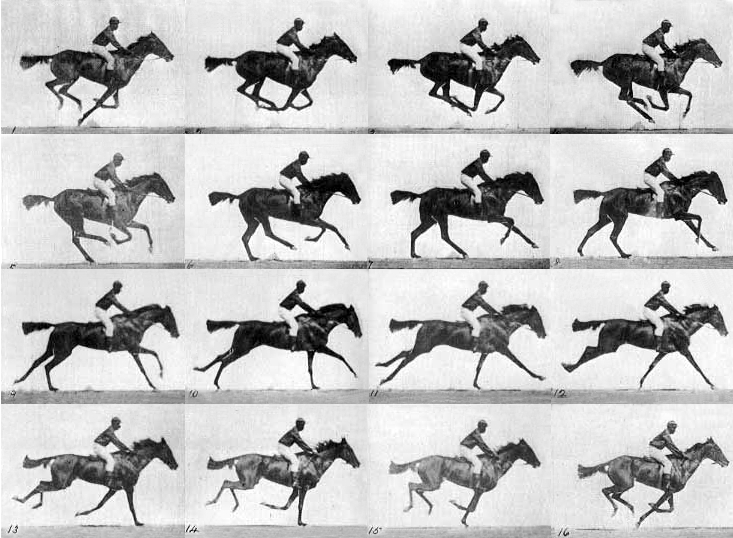

Photography was instrumental in parsing mammalian movement, and mammalian movement is the standard for film, or at least for "natural" looking film. Disjunctive camera movements are taken to be artifice, a technique enabled by the film's mediate status for 1) formally representing a character's subjective state or 2) provoking an excitement-response in the viewer. But avians, it seems, tend to move that way as a rule. I don't have the first hand experience to speak for reptiles, but their philogenetic kinship with birds would suggest that they share motor tendencies. Humans are, in our own eyes, telegenic but not especially photogenic--pictures of humans frozen in motion fascinate us with their absurdity and otherworldliness (Virilio talks about this in relation to sculpture at the beginning of The Vision Machine, I think). I suppose I find it odd, or too nicely coincidental/providential, that the modern hierarchy of being--and the hierarchy of sumptuary restrictions: vegan, vegetarian, pescatarian, chicken eater, beef eater--fits so nicely with biological amenability to film over photography. It is almost as if the horse has escaped classification as a meat-animal by virtue of a blurred fleetness of foot.

No comments:

Post a Comment